Things are not what they seem. Write about this. When she woke up, she retained a dream fragment. She is in a classroom, and someone is writing on the blackboard. There isn’t actually a teacher or even a hand, but somehow the words get written in chalk—multi-colored chalk—and they say:

THINGS ARE NOT WHAT THEY SEEM. WRITE ABOUT THIS.

Merilee loves messages, miracles and personal missives of multifarious stripes and colours. They make her feel that her co-creation with the invisible forces, is intact, resilient, in good standing. Did they not—these invisible helpers and their charming ways of communicating—redeem her from the scourge of personal tragedies which landed with such force on her family’s head?

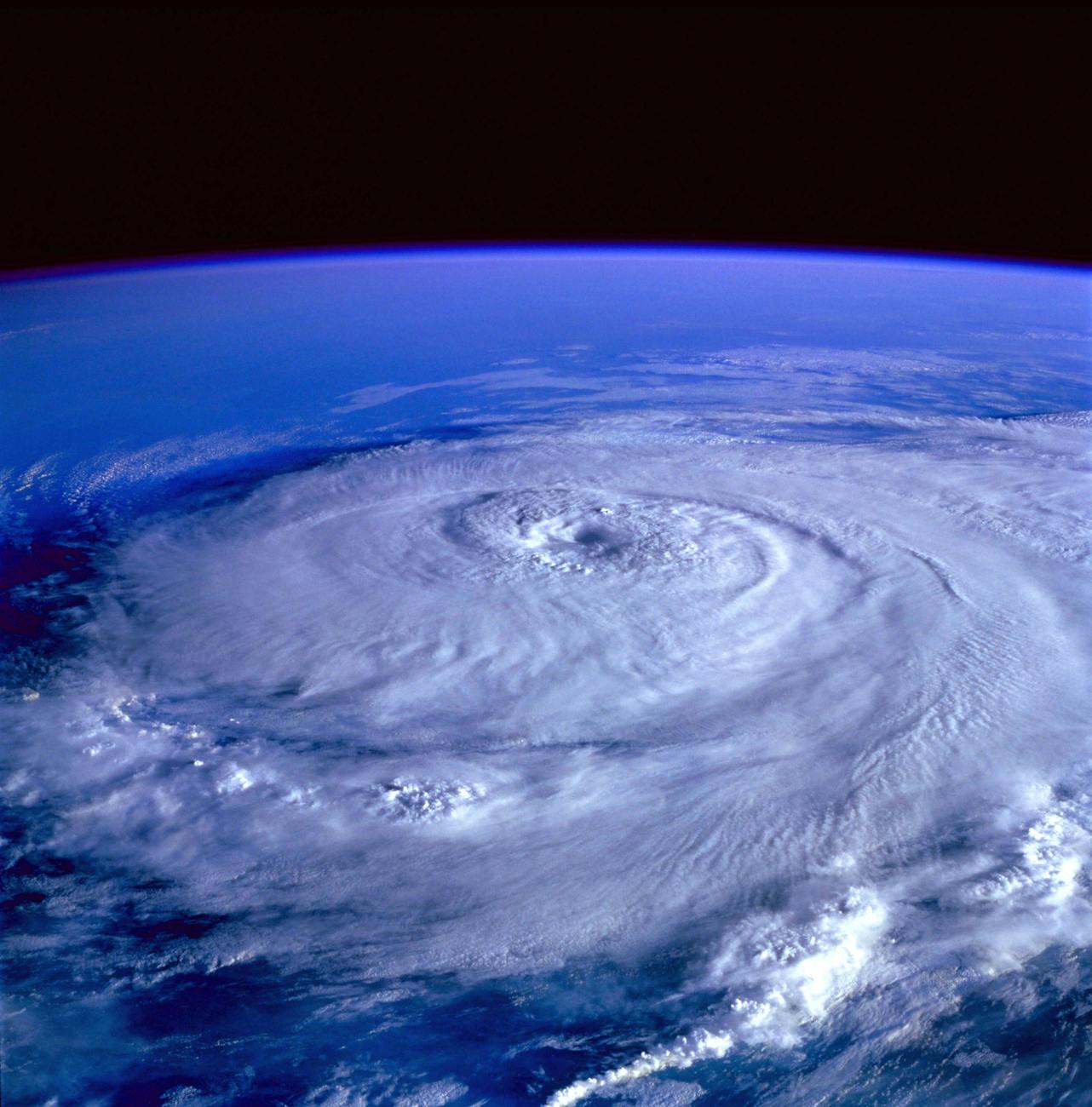

Her husband Owen’s morning routine is to check the blog of Cliff Mass, a resident weather genius at the University of Washington. Professor Mass must never sleep, she figures. He posts complex, continuous, research-dense reports with dazzling charts, stats and graphics, day after day. There is nothing Owen would rather do than be asked about the weather. Merilee smiles, remembering how she used to think that talking about the weather meant you were deflecting emotions. In her ripening years, she prizes the weather as a bridge, a stepping stone, a safe and fertile zone. It invites greater companionability.

This morning Owen is reading aloud to her. It’s about a phenomenon called MID-LATITUDINAL CYCLONES. She loves words. This one calls to her. Owen explains that it means hurricanes which onset in the middle of the continent, but cannot be called hurricanes because they are land-centered and non-tropical. Merilee (Merry for short) thinks: “Mid-latitudinal cyclone. A perfect description of so many wounded people I know.”

What is it about the English language? she muses for the zillionth time—its over-abundance of terms about upset, strife, rupture, dislocation, discontent? She decides to counter by summoning terms that connote wholeness, repair, regeneration, belonging.

At this moment, she is walking along the edge of the estuary, weaving her way through stinging nettles, to Raindrop Springs. One of her favorite pilgrimage spots, a sacred fountain for returning salmon, at the base of Puget Sound. Redolent of the holy waters in limestone crevices of blessed Ireland. She sings “The Song of the Healer” by Sally Oldfield. To the creek, the salmon fry, the bald eagles, the great blue herons and the American dippers.

We sail the rivers of the twilight sun, we have no harbor when our fishing’s done, we have no home but that of the windy mountain, follow the sun till the day is done, and the moon’s on fire! We have a queen, touched our eyes with healing..

She lies down on the spongy bank. Smiling in her half-sleep, she remembers the Taoist master she sat next to on the flight from Portland to Denver. Each was bound for the Denver Gem and Mineral Show. He was telling her about the ancient scrolls of the Taoist immortals. They could still be found in monasteries in far-flung mountain realms of China—monasteries which had wrapped themselves in dense fog and mist, thereby preventing the Red Guard from finding their treasures and murdering their monks.

The wise ones wrote verse after verse on the same theme: earthly life is always poised between blackness and blinding white; shadow and shine; womb and catapult; receiving and initiating. It is the alchemical gift of humans, animals, minerals and trees to live their destinies and marry the seeming opposites. She commented, “My name is Merry—Merry as in merriment. Marrying the opposites. A mysterious blueprint, isn’t it? To be in form but to be expected to become formless?”

“Yes, my dear,” said the master. “But your body and being need to welcome and take into account, the non-seen but ever-felt, non-visible world.”

“You mean,” she said, “You can both be separate and distraught, fractured and whole at the same time?”

He took a card out of his pocket. It had an image of the first quarter moon—a sliver of light that illuminated a forest grove. The caption said: “The moon teaches me, Darling, you do not have to be whole to shine.”

This message filled her with such joyous recognition, she started laughing. The comment brewing in her mouth dissolved and she gave herself over to complete mirth. Her seat-mate maintained his serene half-smile. The flight attendant passing them with a tray of water, started giggling. The cups on her tray started jiggling. A man two rows ahead of them with courtly panache, got up from his seat, saying, “Allow me,” taking the tray from the stewardess. By now she had lost all pretense at composure, had sat down on the extra seat reserved for the crew, dissolved into laughter and tears. The same man who had delivered the tray to safety now offered her a kleenex.

The master looked at Merry with a knowing smile. “I get it,” thought Merry. “The key is not the external condition, it’s the state of mind of the person. That message went right from the moon’s message, to my heart, to fertile fields in the heart of the stewardess and her temporary knight in shining armor.”

Back on the spongy edge of the estuary, Merry’s body soaks in the warmth of the river bank. It serves up an additional neural link as she remembers the river she met in Galway. Festooned with willows just like in The Wind in the Willows. This river has seven different Irish names because it appears, and vanishes, then reappears, at least seven times. They are called disappearing channels.

Her dreamy mind weaves back to the plane flight to Denver. The flight attendant Gracie has pulled herself together and accomplished preparation for landing. No one ever reported her for lack of professionalism. No one said that she lost it. Everyone remembered this as a choice festive moment, when someone was real and dropped their persona. Someone dissolved in joy was a vapor of wellbeing that infused the cabin.

Her Taoist row mate, traveling light, did not proceed to baggage claim. After a mutual bow, she lost track of him. Over the next four days, Merry wove in and out of untold millions of stones and crystals: charoite talismans; 8 foot high sculptures of obsidian; football field sized displays of tiny beads; gigantic boulders of kyanite; mattresses of heated Korean amethyst crystals; Brazilian clear quartz that had been struck by lightning; bracelets, earrings, necklaces, nose rings, talismans with mystical powers. And an unending discharge of stories from the epic intergalactic (it seemed) reunion hosted by Tuscon winter after winter. She had felt buoyant and relieved, relaxed and content since her plane flight. She had forgotten about Master Toomtok.

Until she entered the moon-gazing room which looked out through the wall-to-ceiling glass at at the play of pink and yellow lightning arrows in the high desert that was Denver. She had enrolled for a workshop called How Stones and Crystals Interpenetrate with the Unseen. When she looked up to see the instructor of the session, whom did she behold but Master Toomtok. He cast at her his gentle smile-beam, and winked.